|

|

|

|

Tamed from its early beginnings

when it consisted of wildly flowing rapids, the River Douro is now placid

in most places, creating ideal cruising conditions.

Ardent Portugal lovers say that the only way to see the Douro is by train or boat, as the road veers away from the river for almost two thirds of its length. Passenger carrying boats run from Porto, Regua and Pinhao and an eight day cruise is also available. I have always wanted to be one of the first recreational skippers to cross the width of Portugal, and when the opportunity arose, I immediately decided in favour. Any uprising of ‘guilt’ I assuaged by resolving to call in at clients owning Manor Houses in the Douro Valley. That done, my conscience was clear. We made our journey in June with the green and fertile surroundings of early summer. Other seasons enchant with their own attractions, in February, the almond trees come into flower; their pale, white blossoms in startling contrast against the greens and browns of the background. The brilliantly coloured bee-eaters have their nesting season in April and they fly over the river while searching for a suitable site in the clay galleries that slope down to the river in certain spots. Late September and beginning of October herald the grape harvest with vineyards full of workers picking the grapes and transporting them to the quintas (wine producing farms). I drove from my home in Viana

do Castelo to rendezvous with Wigwam at Povoa de Varzim, a few kilometres

from the entrance to the Douro River. Wigwam is a Warrior 35 and a venerable

ocean cruiser. Roger who had just sold his boat agreed to accompany

me to take her to Povoa. On an 11 metre craft, we anticipated a comfortable

trip, and aside from minor problems, we had none.

We tied up in the Ribeira area, which is classified by UNESCO as a World Heritage site. We moored near the Porto Carlton Hotel using a part of a group of buildings constructed on a section of the mediaeval city wall dating back to the 16th Century. The colourful neighbourhood with its variously hued buildings is most attractive and reflects a distant, irretrievable heritage. Despite the presence of protective dams along the river, there is always the possibility of a flood. Porto Carlton designers have anticipated the Douro’s vagaries and tendencies to inconvenient flooding and the hotel is designed to function, even if the entire ground floor were to be flooded. Porto merits a longer stay

and our fairly tight schedule, only allowed the pleasant obligation of

a visit to a Port Wine lodge.

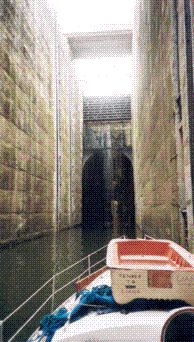

After a simple but delicious dinner with local wine, we went to bed anticipating the ‘real’ beginning of the voyage. Wigwam’s draft was greater than the majority of the passenger carrying river boats plying the river. The recently opened waterway is designed to accommodate seagoing vessels with a maximum length of 83 metres, a width of 3.8 metres and, because of the bridges, an air height of only 7 metres. For cruising yachts such as Wigwam, the latter necessitates temporary removal of the mast. A problem, albeit slight, arose from this separation of mast from yacht since the VHF radio aerial was mounted on top of the mast and we had to rely on mobile phones for communication. Water and electricity had not yet been connected on the pontoons and we recharged the batteries while having our evening meal. To ensure time for a maximum charge a few additional glasses of Port Wine were consumed. The scenic changes along

the Douro are as dramatic as ever; only the journey has improved with the

addition of more than half a dozen dams over the past few years.

Our first day out was fairly uneventful, giving us the opportunity to orient both the vessel and ourselves to unfamiliar rhythms. We were greeted by bright sunshine the next morning; it was welcome but short-lived that day but after this, the sun shone from a cloudless sky. Booked to go through the first dam at 10.45, we looked forward to having breakfast in the waiting area. We tied alongside a large river boat in the lock. Our adult enthusiasm couldn't match that of 200 school children, who gave a mighty cheer when the lock gates shut. Their school outing was to Regua by boat - far more exciting than the return trip on a coach. As we were talking to the pretty teachers, the 10 minutes to wait for the huge lock to fill passed very quickly. “Goodbye, goodbye, Wigwam ” cried the P.A. system, immediately echoed by the exuberant children as their boat moved out into the river. I wanted to visit the Convento de Alpendorada, one of the most important buildings in the area. On a previous visit by car,

I had been shown a bay - the site of a proposed marina. We found this bay

but without any sign of the marina, so we returned to a pontoon at Bitetos,

from which I took a taxi to the convent

When I returned to Wigwam, I found it dwarfed by a large hotel boat tied up nearby. The Vasco de Gama carries 120 passengers, mostly German and French. At the small village, supply was unequal to demand: three small bars (one closed) and a basic grocery shop comprised the amenities. The choice of this place as their overnight stop seemed odd. When we went out later, we found the bar called Cafe Francais full (its four tables were occupied) of patriots from Vasco de Gama. They seemed quite happy to be tippling port decanted from an unmarked flagon but served from a labelled bottle. Whether their good humour would survive entrance into a new day was another question. In any case, they returned to their boat for dinner, not to be seen again, while we went on to the other bar for our own meal. The next day, we cruised from Bitelos to Regua. Cruising towards the lock at Carrapetelo (one of the largest locks in the world), 18 kilometres upstream, we had left a good margin of time in case we had unforeseen problems, but our complacency soon evaporated. As the channel narrowed, the current became stronger. At times we were battling to achieve even 1 knot per hour. Adding piquancy to the struggle,

a motor cruiser barrelled past at 30 knots, rocking the 11 tonnes of Wigwam

from side to side. We lost little except our tempers, although we discovered

later that a line and bucket had been swept overboard.

A modern version of the traditional ‘rabelo’ soon joined us. Rabelos used to transport the wine to the mouth of the Douro where it was aged and blended. The river trip was fraught with danger and many ended in shipwreck caused by the racing rapids. The railway was later constructed to carry the wine and now, tanker lorries carry it by road. The boats still exist, and every year there is a rabelo race in early June organised by the Port Wine houses. Using the final stretches of the Douro to Porto, it is a tribute to the old days and to the keen boatmen who rushed the wine to the sea. At Mesao Frio, we experienced a dramatic change in geology, which up to that time had consisted of wooded valleys and the occasional village with new pontoons coming out from the shore. Pastoral and fairly peaceful. From a rugged granite valley relieved by the presence of small vineyards, we now found the river bordered on either side by the famous vineyards of the Douro. The ‘soil’ is sedimentary

‘schist’ rock and is known for its ‘geios’, the terraces and steps that

lead downward to the riverside. This is one of the oldest wine producing

areas in Europe and we passed many white-washed ‘quintas’, their Port Wine

house names prominently displayed.

The total cost of the river dues and the locking of the boat through the five locks upriver and return was very reasonable at just under 100 Euros. That afternoon we went through the Regua dam and then on to Pinhao, which has supplanted Regua as ‘capital’ of the port wine growing area. At one point, the Quinta de Ferradosa was directly above us. The owners are Messias Port and a pontoon serves visitors who want to tie up, take a wine tour and taste the products. We noted it for a future stop and continued up river. As we moved further east, the river banks became less cultivated and more mountainous. Noteworthy in the journey

is the river’s long meander to Foz do Sabor. The railway line cuts

through a tunnel and there are no roads along this section, resulting in

countryside completely unspoiled by man.

Tying up at the pontoon, we made our way to the village. There, the busyness was explained An Italian television team was in situ to make a film about the Foz Coa Archaeological park. They were about to eat dinner so we sat at a neighbouring table and enjoyed the evening meal of barbecued river fish, potatoes and salad. When the Portuguese authorities were building dams along the Douro in the 1980s, prehistoric rock shelters were discovered during excavations at Foz Coa. An enormous public debate and international pressure caused a partial halt to excavation. The Vila Nova de Foz Coa composed a rap song called (‘Petroglyphs Can’t Swim’) which helped turn the tide, so to speak and, in November 1995 the dam was stopped and the area became a World Heritage Site. (Contact the Park authorities before planning a visit.) Our next lock was Pocinho, a short distance from Foz do Sabor and we then continued through the unspoilt river valley. The river scenery is completely unspoilt with the songs of birds in the almond and olive trees on the bank coming across the water. High above there were usually birds of prey hunting and, on one occasion, one took a fish from the river near the boat. As we neared our last stop in Portugal at Barca da Alva, the new road bridge was support for the nests of thousands of swallows which swooped over the river. A precocious decision to spend the next day, Portugal’s National Day of Independence, at Vega Terron in Spain resulted in a small series of disappointments; possibly divine retribution for our disloyalty to our host country and, after one hour we were back again, moored in Portugal. We had to hurry back to Pinhao since two more Manor House visits were arranged. At Pinhao, we started the

day by shaving the stubble accumulated during our voyage and dressing in

our best clothes for our first visit.

The other Manor House, Casal de Loivos, is situated in hills which slope down to the river area. It is distinguished by BBC television as having one of the best six views in the world. A very good meal with the owner was washed down with the wine and Port produced from their own grapes. We then returned to the boat and continued downstream to the village of Covelinhas. Next morning we passed through the lock at 9.30am and spent a lazy day on Wigwam at Regua. We were able to have showers in an unfinished building and generally improve our sailors’ image before I set off to have dinner at Quinta de Santa Julia de Loureiro, a Manor House and wine-producing quinta whose wines are consistently among award winners at international competitions. Guests at this Manor House

are favoured by wonderful views of the terraced land of both their hosts

quinta and nearby properties.

At several points, I had seen large machines carving up new terraces on the hillsides without any retaining walls. I asked my host about this and he explained that slaves built the old terraces centuries ago – not publicised by the Tourism department! Present husbandry now requires tractors to work the vineyards, making the walls a definite deterrent in addition to their being extremely labour intensive to maintain. Picking is still done by hand, due to the delicacy of the fruit. The best Port is still crushed by foot in huge vats so that the pips are not crushed to add a bitter taste. A fascinating comment made during dinner was that the two manmade features visible by naked eye from the moon are the Great Wall of China and the terraces of the Douro valley. Our last two days on board were spent returning down river to Porto stopping overnight at villages and having ample meals at the small restaurants. After a second overnight stop in Porto we set off cheerfully on 15 June for the short sea trip under motor to reunite Wigwam with her mast. I have always enjoyed navigating rivers, as there is so much to see and do. This particular trip will remain one of my favourites. The tranquillity of the river, lack of other craft, riverside facilities, friendliness of the people, spectacular scenery, good food and wine, warm weather, breath-taking but easy locks, three UNESCO World Heritage Sites plus a natural park - all situated along this 200 kms. of navigable water. David Lumby and Carla Harvey |